SERPICO

The Struggle to Rid Manhattan of Police Corruption

By Joyce Gold, Manhattan Historian

Frank Serpico is best known for whistleblowing about police corruption. He became the first New York City police officer in history to testify about widespread corruption in the department. His story is all about the risks of taking a stand and the subsequent consequences. The youngest son of Italian immigrants, he was a member of the police department from 1959 to 1972, joining after serving two years in the US Army in South Korea. Serpico was a good cop better known in local communities as “Paco.”

Serpico came to realize that his squad and much of the police hierarchy above it appeared to be corrupt. He was in an untenable position of having to either report the illegalities of his fellow officers or join them. In whatever precinct he was assigned, he observed and reported corruption and was increasingly frustrated about getting the police department and/or the government to do anything about it.

Serpico resisted joining in his colleagues’ crimes but was forced to accompany fellow plainclothes officers as he witnessed their violence, extortion, and collecting payoffs. Yet, he refused to accept his share of the money.

He was never considered part of the police team. He was misunderstood when he moved to Greenwich Village. Because of his appearance and interests, colleagues accused him of being homosexual. Serpico requested a transfer. At his new precinct, Serpico worked in plain clothes. Despite fearing for his life, he kept reporting illegalities but got neither satisfaction nor protection.

Serpico befriended police Sergeant David Durk, who had been assigned to the Mayor’s Office of Investigations. Serpico was offered a bribe and informed Durk, who arranged a meeting with a high-ranking investigator. Serpico was told that he must either testify or “forget it”. He turned the bribe over to his sergeant. Serpico then requested a transfer and recorded his phone calls.

He was reassigned to yet another division but immediately discovered corruption there also. He informed on their activities and was assured that the police commissioner wanted him to continue gathering evidence and that the chief’s office would contact him.

Serpico became impatient waiting for the promised contact. He and Durk went to the mayor’s assistant, who promised a real investigation and support. Their efforts were stymied by political pressure. Durk suggested they go to other officials or even the press, but Serpico dismissed the idea. The district attorney led Serpico to believe that there would be a major investigation into rampant department corruption if he testified to a grand jury.

During the grand jury trial, the district attorney prevented him from answering questions that pointed up the chain of command. Serpico became even more frustrated.

Knowing his life was in danger, he, Durk, and an honest division commander reported the corruption to The New York Times. After the allegations were printed, Serpico was reassigned to a dangerous narcotics squad in Brooklyn, where he found even greater corruption and danger.

His personal life suffered from the strain. He began dating Leslie, a woman in his Spanish class, but she left him to marry another man. He began a romance with his neighbour Laurie. When colleagues tried to convince him to take the payoff money, and he declined, the strain took a toll on him and his relationship. As the investigation proceeded, Serpico was threatened by the squad, and Laurie left him as a result.

On February 3, 1971, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Serpico was shot during an arrest attempt when his backup failed to act. The bullet severed an auditory nerve and left bullet fragments lodged in his brain. He recovered, though with lifelong effects from his wounds.

The circumstances surrounding Serpico’s shooting quickly came into question, even raising the possibility that Serpico had been brought to the apartment by his colleagues to be murdered. Albeit no formal investigation was initiated.

Serpico and Durk brought about a major change to the police department. Largely a result of the publicity generated by their public revelations of police corruption, in April 1970, Mayor John Lindsay formed the Knapp Commission. It was officially called “The Commission to Investigate Alleged Police Corruption.” It concluded that the NYPD had systematic corruption problems and confirmed the presence of widespread corruption. They made a number of recommendations.

An immediate result of the witness testimony, criminal indictments against corrupt police officials, were handed down. Soon afterwards, the mayor appointed Commissioner Patrick Murphy to clean up the department. He was tasked to begin integrity checks, transfer senior personnel on a huge scale, rotate critical jobs, ensure enough funds to pay informants and crackdown on citizen attempts at bribery.

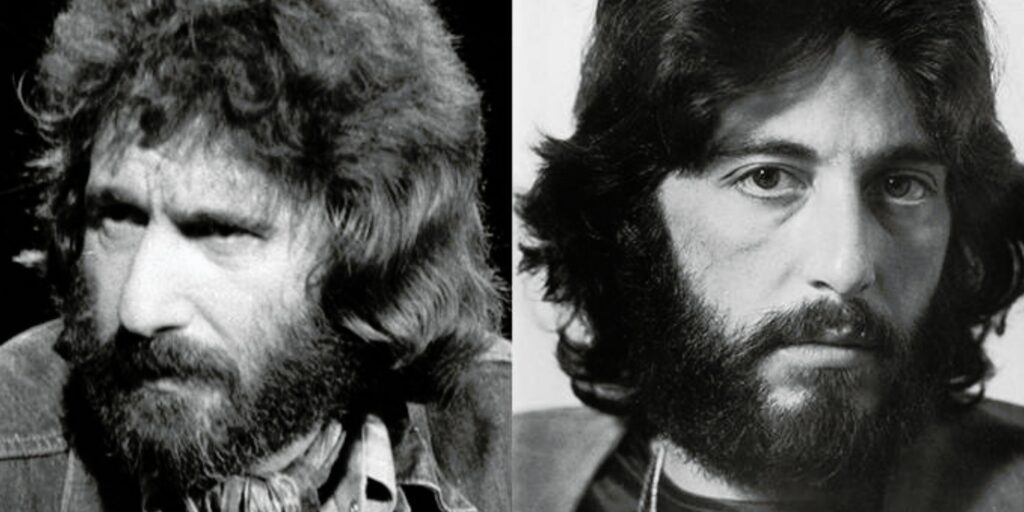

After this incident, Serpico received a detective’s gold shield and the New York City Police Department’s highest honor, the Medal of Honor. There was no ceremony; it was simply handed to him over the desk. One month later, on June 15, 1972, Serpico retired. He left for Switzerland to recuperate, spending almost a decade living there and on a farm in the Netherlands while he travelled and studied. He also took Italian citizenship. Film star Al Pacino initially did not find the initial film script interesting.

A re-worked script convinced him to consider the part. Pacino met Serpico, which fully convinced the actor to accept the part, particularly because of the following conversation: Pacino asked Serpico why he had acted as he had. Serpico’s answer was, “If I didn’t, who would I be when I listened to a piece of music?” Pacino was further moved by Serpico’s conviction to reform the NYPD and became more committed to the project.

The film was released in December 1973. Serpico attended the premiere but left before the ending.

Serpico felt distant” from the final version and criticized that it “Didn’t give a sense of frustration you feel when you’re not able to do anything.” Not until 2010, over 30 years after its completion, did Serpico watch the film in its entirety.

As a result of Serpico’s efforts, the NYPD was drastically changed. Michael Armstrong, who was counsel to the Knapp Commission and went on to become chair of the city’s Commission to Combat Police Corruption, observed in 2012, “The attitude throughout the department seems fundamentally hostile to the kind of systemized graft that had been a way of life almost 40 years ago.”

Serpico took a risk, at great cost to himself, but felt he would lose himself if he hadn’t. Now eighty-five years old, Serpico lives in a log cabin in upstate New York. Bullet fragments still lodged in his head remind him of his bold and groundbreaking courage fighting injustice.

Joyce Gold is president of Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, specializing in in-depth private walking tours of many city neighbourhoods. Email: [email protected] Call: 212 242 5762